“During the school day, we shouldn’t see [phones].” This is how Madeleine Echols, Emery/Weiner dean of students, describes one of the biggest changes for students going into the 2024-2025 school year: the new phone policy. Administration revealed this new policy in an email sent around mid-August, just a week before the official start of the semester. According to the official language of the EWS Student/Parent Handbook, linked in the email, the school day is “7:45 a.m. to 3:30 p.m.,” which encompasses office hours, study hall, lunch, snack, passing period, and of course, class, now all phone-free times.

Last school year also began with a new phone policy: phone homes, which consisted of coming into class and dropping your phones in a labeled shoe organizer, where they would remain for the whole class period. However, phones were allowed during most other times of the day. Echols believes that this change in policy, “takes the guesswork” out of it, no more telling students “‘you can use it during this’ but ‘you can’t use it during this.’”

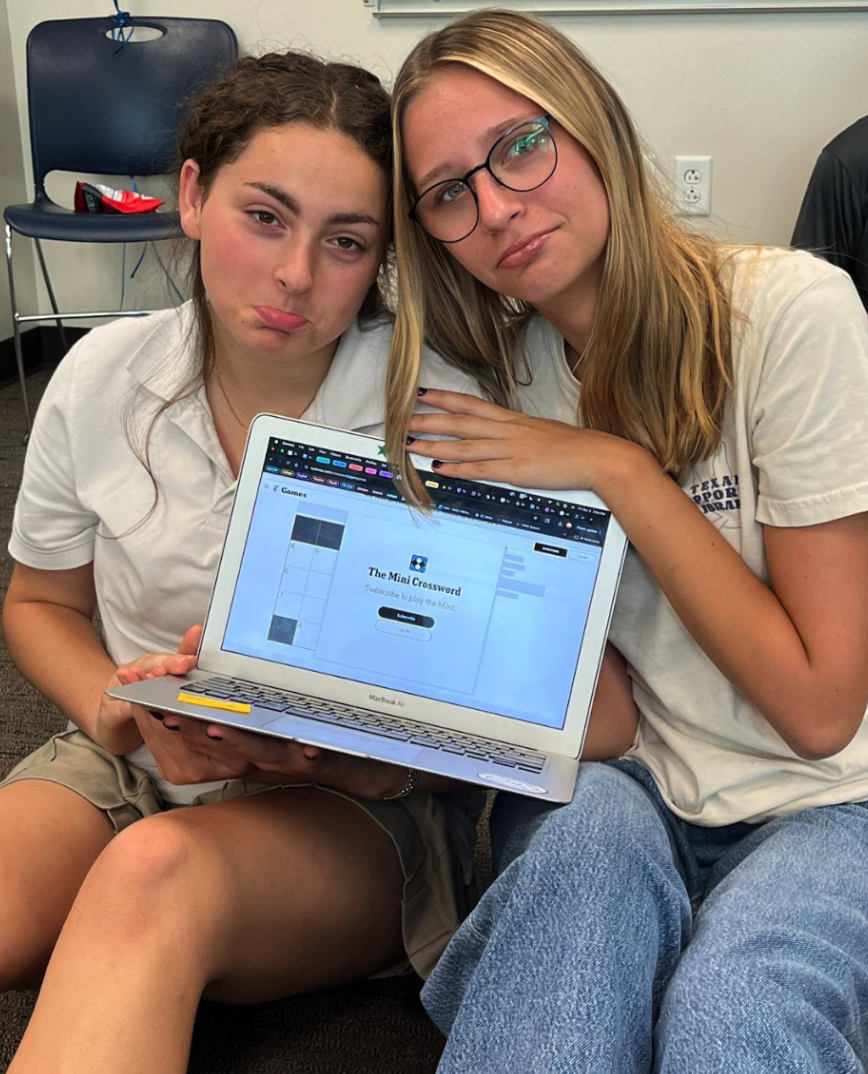

Even as the administration consistently maintained and exhibited a positive outlook on the policy, student concerns began to fly as the school year approached. Sophomore Marisa Yanosik admitted that she missed “being able to play music while [she] works.” However, many teachers still allow students to listen to music as long as it is played on their computers. Yanosik further stated concerns, saying, “I feel that using our phones can be a way to decompress throughout the day, which is sometimes necessary to be able to do during … lunch,” a sentiment echoed by many other members of the student body.

Despite these worries, Echols notes a positive impact on lunch without phones, saying, “Lunch … feels totally different. [Students] are engaged, and talking, and having fun.” She even suggests the cafeteria has been cleaner because students are paying attention to their surroundings more without their phones.

Upper school social sciences teacher Holly Daniel has also seen the benefits in the classroom. She says her students have seemed “more focused and more participatory” because their phones are “not an option.”

This policy not only affects students though, as administration also suggests faculty try and limit their phone usage during the day to present a good example to students. Daniel says that she has been more “mindful about using [her phone] less.” And Echols echoes this statement, believing it has been “really nice to leave [her] phone in [her] office and really be present.”

With the school year still in its early stages, there is still time to see how this mandate develops and works in the practice of everyday life. For now, Echols suggests that everybody “live in it for a minute, … take some time, see what it’s all about, and then … have the discussion.”

There’s certainly part of this new policy that feels like an experiment with uncertainties that will need to be faced together and results that will be discovered as time goes on. People are still uncertain about the effects of phones on communities as a whole. As technology changes and new policies arise, some may point out the benefits of phone-free time, and others may focus on the importance of phones in everyday, modern life. For now, though, it is important to understand that this policy is new for everyone, an experiment everyone is undergoing, and it should be taken one day at a time.