“Murder Hornets” in America: Fact and Fiction

May 11, 2020

The headline that’s been sweeping the nation for the past few days seems to be straight out of a science fiction movie: Murder Hornets Found In America! However, the truth is a lot less sensational.

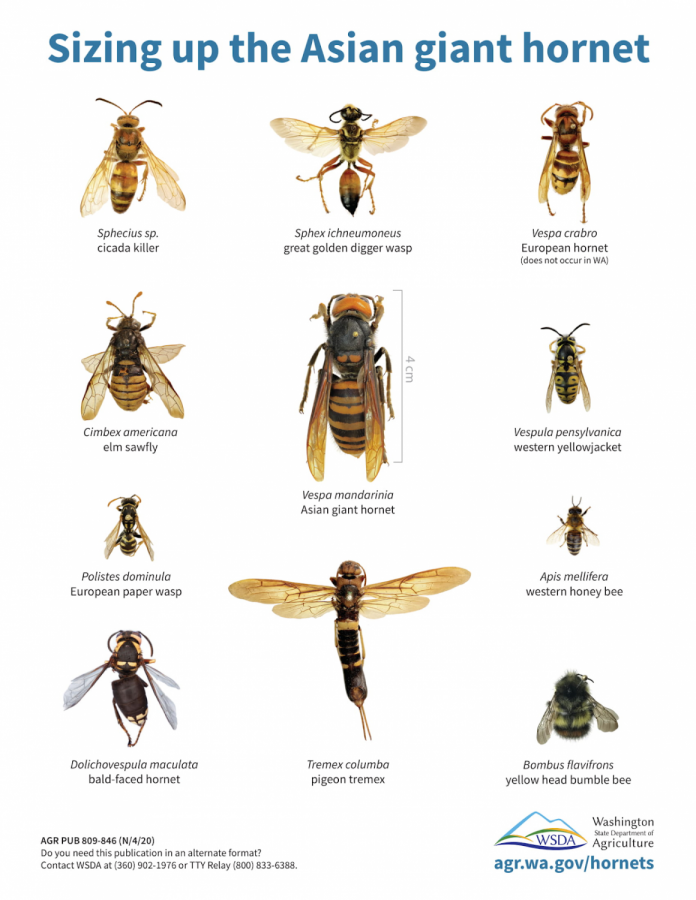

In Dec. 2019, the Washington State Department of Agriculture confirmed a reported sighting and a dead specimen of the Asian Giant Hornet (Vespa Mandarinia) in the border town of Blaine. These sightings happened months after the British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture confirmed that a nest was found and destroyed on Vancouver Island in the city of Nanaimo in Sep. 2019. This April, Washington State authorities asked the public to report any sightings of the hornet, who’s nesting cycle begins in mid-April.

The Asian Giant Hornet is the world’s largest hornet species, at around 2 inches in length with a 3 inch wingspan. The hornets are native to East and Southeast Asia, with a subspecies in Japan, and they prefer to live in low mountain or forest areas while avoiding plains and high-altitude areas. They are a eusocial insect like bees and ants, and they feed on a wide variety of insects like bees and mantises.

It is unknown exactly how either the Canadian nest or the specimen found in Washington made it to North America but the most likely method was via cargo ship. It is highly unlikely that the hornet flew by itself to America as it would have exhausted itself and died on the long journey

It’s also unknown exactly how many Asian Giant Hornets are in America. It is possible that the dead specimen found in Washington was alone and did not establish a colony. It is also possible that there is a colony in Washington and that there are other hornets. The Washington State Department of Agriculture has established an extensive public outreach program that includes working with local beekeepers and entomologists to determine if the hornets have established themselves in American and to what extent.

A single Asian Giant Hornet sting will not kill someone unless they have serious allergies. However, if the insect is provoked and others are in the area, they could swarm, with dozens of hornets stinging multiple times. In Japan, around 50 people per year die due to attacks from Japanese Giant Hornets. The hornet’s stinger is around one quarter of an inch long and due to its size, it can deliver a large and painful dose of venom.

“The pain is excruciating,” says Wildlife educator Coyote Peterson, famous for his insect sting videos. The sting of the Asian Giant Hornet is the second most painful insect sting Peterson has ever recieved. “It feels like someone has shoved a red hot poker into your arm and does not remove it for close to six hours,” he said. Peterson ranked the insect a four, the highest level, on the Schmidt sting pain index, a pain scale which ranks the sting of various insects (for context a honey bee ranks at a two).

Right now, it is unlikely that the hornet will establish a foothold in North America, much less spread across the continent and terrorize Americans. Entomologists, beekeepers, and state officials in Washington are working hard to survey the problem and figure out the best solution. Even if the hornet does establish in North America, it will be a much larger problem for bees than for humans.

When Asian Giant Hornets attack a beehive, they enter into an all out rampage. Using their large mandibles to decapitate bees, a single hornet can kill 40 European honey bees in only a minute while a group of 30 can destroy an entire hive containing 30,000 bees in one hour. Honey bees in Asia have developed a defense against the hornet where they surround the hornet and beat their wings to kill the hornet with their own body heat but American honey bees are defenseless. Honey bees play a crucial role in pollination, and the introduction of such a voracious predator could pose a threat to the environment and food supply.

Although it might seem like a huge problem, “you shouldn’t worry about it,” said Floyd Shockley, the entomology collections manager at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, “Is it possible that a few beekeepers are going to lose their hives? Yes. I can’t rule out that possibility. But is it going to be global devastation? No.”